After using profanities and pounding on the computer keyboard with his fist because he couldn’t get it “unfrozen,” Tommy stated that he “Should have inhibited his impulse and found an alternative, more productive response.” While he used the correct label for the Habit of Mind, Tommy’s response was in the past tense; reactive—what he should have done. We want students to employ the Habits of Mind proactively—in the future tense—how they will employ these dispositions.

Dispositions may take many years to become internalised. For some, it’s a lifetime endeavour. For others they are born with the inclination, for still others dispositions are used only when reminded and for some it is a life-long but elusive quest. When students use the Habits of Mind proactively, it is an indication that the disposition has become “internalised.” This article offers some strategies of helping students “interiorise” the Habits of Mind.

Strategies to “Interiorise” the Habits of Mind

To be successful, students must come to “own” the dispositions. Strategies teachers can use to cause students to internalise dispositions include:

1) Consistent Vocabulary: Developing a common and consistent vocabulary throughout the culture of the school and classroom. Names and labels of dispositions provide conceptual tools for students and staff with which they can communicate, operationalise, define and categorise behaviours. The names are heard across all disciplines, on the playground, at home and in the cafeteria.

2) Disposition Density: Repeated and frequent hearing about and focussing on the disposition over time. “Yes, we are going to focus on listening with understanding and empathy again during our class meeting today. I know we did this during our last class meeting as well, but we agreed that listening without interrupting was difficult and you said that several times you forgot and responded impulsively without thinking. Today, let’s become even more aware of our listening and pay attention to what we tell ourselves when we are tempted to interrupt.”

3) Attention to Intention. Drawing attention to and finding the disposition in many settings, in varied circumstances,

contexts and situations. Martinez says that “Besides thinking interdependently in the weight room, when and where else might it be important to think interdependently?”

4) Dispositional Dialogues. Discussing what the disposition means, and having students generate lists of attributes, and envisioning mental pictures of what the disposition looks like and sounds like. “So, while you are working through this problem together, what might it look like and sound like if you are thinking interdependently?”

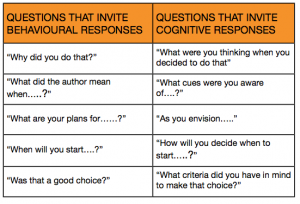

5) Cognitive Questions. Teachers ask a myriad questions many of which are behavioural. To interiorise the Habits the questions must engage the mind (rather than behaviour). For example:

6) Spectators of their Own Thinking.

If teachers pose questions that deliberately engage students’ cognitive processing, and let students know why the questions are being posed in this way, it is more likely that students will become aware of and engage their own mental processes. They become spectators of their own thinking. For example:

- What was going on in your head when…..?

- What were the benefits of…..?

- As you evaluate the effects of…?

- By what criteria are you judging?

What will you be aware of next time…?

Students also become spectators of their own thinking when they are invited to monitor and make explicit the internal dialogue that accompanies the dispositions. For example, “What goes on in your head when you think creatively?” Or, “What did you hear yourself saying inside your brain when you were tempted to talk but your job was to listen?

7) Establishing Expectations. Students are expected to behave in a manner consistent with the disposition and positive feedback (not praise) is given when it is observed. An example from Dweck is, “Your persistence paid off! You stuck with it until you completed your task. You really remained focussed!”These are some of the powerful strategies that get the disposition inside of the brain: otherwise known as “interiorising.”

In summary, internalisation means that these dispositions or mental disciplines serve, as an internal compass that guides decisions when human beings are confronted with dilemmas, enigmas, problems, conflicts or ambiguities. When confronted with problematic situations, students, parents and teachers might habitually employ one or more of these thinking dispositions by asking themselves, “What is the most intelligent thing I can do right now?”

How can I learn from this, what are my resources, how can I draw on my past successes with problems like this, what do I already know about the problem, what resources do I have available or need to generate?

How can I approach this problem flexibly? How might I look at the situation in another way, how can I draw upon my repertoire of problem solving strategies; how can I look at this problem from a fresh perspective?

How can I illuminate this problem to make it clearer, more precise? Do I need to check out my data sources? How might I break this problem down into its component parts and develop a strategy for understanding and accomplishing each step?

What do I know or not know; what questions do I need to ask, what strategies are in my mind now, what am I aware of in terms of my own beliefs, values and goals with this problem? What feelings or emotions am I aware of which might be blocking or enhancing my progress?

The interdependent thinker might turn to others for help. They might ask how this problem affects others; how can we solve it together and what can I learn from others that would help me become a better problem solver?

These dispositions transcend all subject matters commonly taught in school. They are characteristic of peak performers whether they are in homes, schools, athletic fields, organisations, the military, governments, churches or corporations. They are what make marriages successful, learning continual, workplaces productive and democracies enduring.

The learner’s brain continually sculpts itself, (otherwise, neuro-scientifically known as “auto-plasticity”). Because dispositions are never fully mastered, as maybe understanding content and concepts are mastered, the purposes of teaching them to students is to monitor themselves, confront themselves with self-generated data and reveal to others how well they have learned to cope with adverse situations and challenging problems. It means setting goals for themselves to constantly improve their decisions and actions and making commitments to pursue those goals in future situations. It means being alert to feedback by self -observation, seeking feedback from others and modifying their actions to become even more efficient in the execution of their dispositions. It means self-modification – building your own new neural pathways.