Moving Students From Telling to Asking

While the valid use of the word ‘unGoogleable’ is highly debated in my staffroom, my students know an unGoogleable question to be a BIG one: A question that cannot be answered without breaking it into smaller parts, requiring synthesis and deep thinking to answer. If we get the question right, Google will not be able to answer the question. Imagine that!

In a previous Teachers Matter edition, I wrote about the importance of explicitly teaching curiosity and using provocations as a stimulating environment in which to do

this. Questions that stem from curiosity are the catalysts of understanding, discovery, problem solving and innovation in our world. The big questions are those that have not been answered already or are open ended in nature so that multiple answers are possible. They can postulate a new theory, drive a unique inquiry, develop a new perspective, derive an innovation or solve a wicked problem. The important question for us as teachers is, “How might we teach students to ask BIG questions?”

My job sometimes lands me in the bubbling class of year three and four students, where my first realisation was the necessity to teach the words which questions begin with and the mark with which questions close. This may seem obvious to most junior teachers, but as my usual students were intermediate age and older, I was surprised to discover students stating facts when I invited them to be inquisitive. Even when sharing morning news or experiences, it is surprisingly common to hear students share their insights or offer their own connections rather than inquire to gain more information. The good news is if the students don’t have basic questioning skills already, they can pick it up very quickly with some question dice or cards as prompts. Increasing the opportunities for questioning in a range of contexts can establish a strong foundation for our students to build upon. Age old activities such as hot seating, freeze frames, interviewing visitors, 21 questions, mystery bags, Guess My Number and Who Am I? can easily establish inquiring patterns. Interestingly, although these games will not require very many BIG questions, they are still unGoogleable in nature since the Internet will not know who is written on a card stuck to your head, nor what object is hiding in the teacher’s bag. Generally, you will need to synthesise smaller pieces of information in order to guess the person or item.

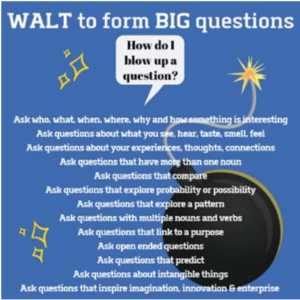

Experiencing the fast progress of young students moving from statements to questioning is encouraging, but how do we keep the progress rolling in consecutive years, leveraging the explicit teaching of the previous teachers, resulting ultimately in students formulating BIG questions? Since questioning levels can be such an abstract concept for students to grasp, I developed a metaphor of a bomb to represent the ‘blowing up of a question,’ where the fuse represents a continuum of questions from basic to deep. An accompanying poster outlines possible next steps

to graduate along the continuum. Again, using these tools in a range of contexts repetitively can bring about opportunities for students to assess and grow their questioning skills. The ‘blowing up a question’ model can be used while analysing real world maths problems, exploring inquiry themes or scientific concepts, developing ‘genius hour’ projects, or in reciprocal reading groups.

Question grids are also invaluable tools for teaching and learning about questions. I have a growing number of laminated grids attached to my wall for fast and regular reference, not

to mention in every other classroom I visit in a week. They are particularly useful for intermediate age and upward to use in an independent and group manner as well as for class discussions where we determine which question starter combinations will help us to specialise in such things as comparing, predicting, developing perspectives or allowing for multiple answers.

My students learn quickly what section of the grid represents questions that are easily researched, require their own thinking and those that are unGoogleable, Big questions. A common challenge with some students is the quick switch to answering the questions they ask. When the lesson objective is to ask, I encourage students to keep that focus rather than begin answering. When students hear their questions answered by other students straight away, it may jeopardise a safe environment where students feel they can take risks. Albert Einstein once said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask.”

I challenge teachers to facilitate at least one learning session that is entirely dedicated to the art of questioning. You willno doubt be hooked as you become familiar with where your students sit on the fuse continuum and how much potential exists to progress them. Similarly, I challenge leaders to conduct an experiment with your staff. Do they know what a BIG question is or the importance of building of forming one? Many professional development courses concentrate on developing teacher questioning. I wonder why the questioning is left only to the teachers when it is the students who should be directing their own learning?

While questioning is an important skill that can articulate our curiosities, it is also important to know what to do with a BIG question once the best ones have been crafted. For if we can empower students to ask questions whose answers have not already been shared or exhausted, we just might unveil new knowledge. In the next edition, I will explore the process of constructing that knowledge. I hope you, your students or staff will have BIG questions ready and waiting.

“Surely, it makes sense for teachers to be dedicating time in their classrooms to explicitly teaching, assessing and nurturing well articulated, inquiring minds.”